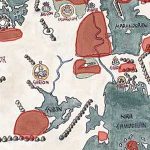

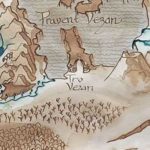

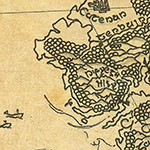

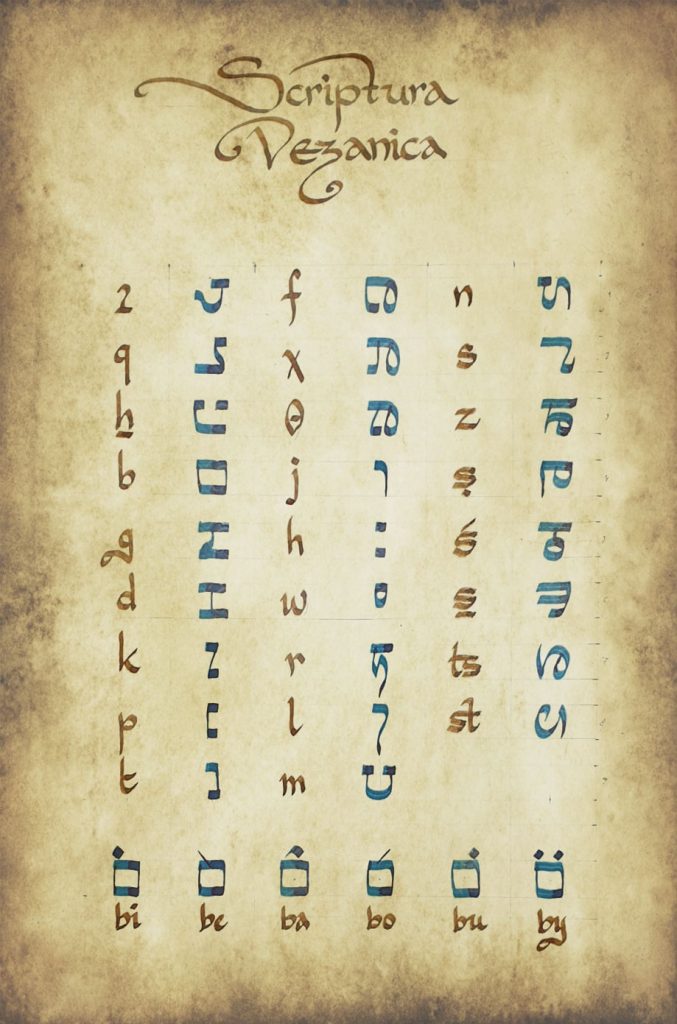

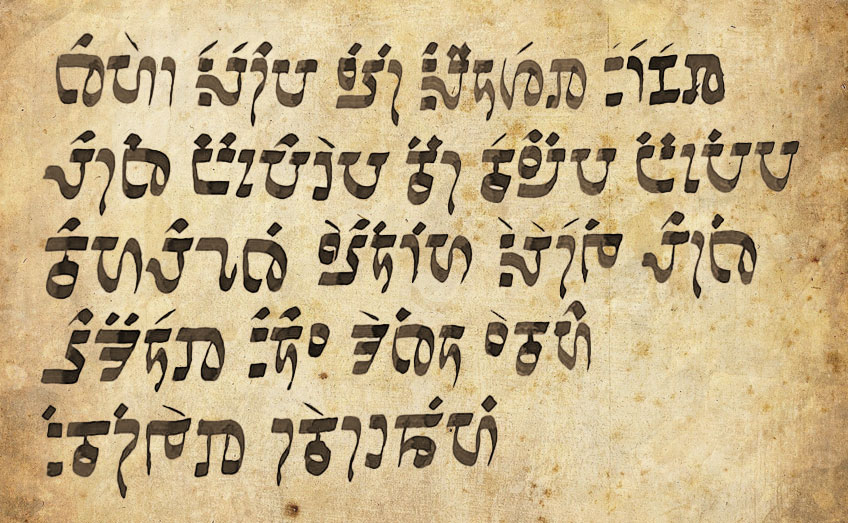

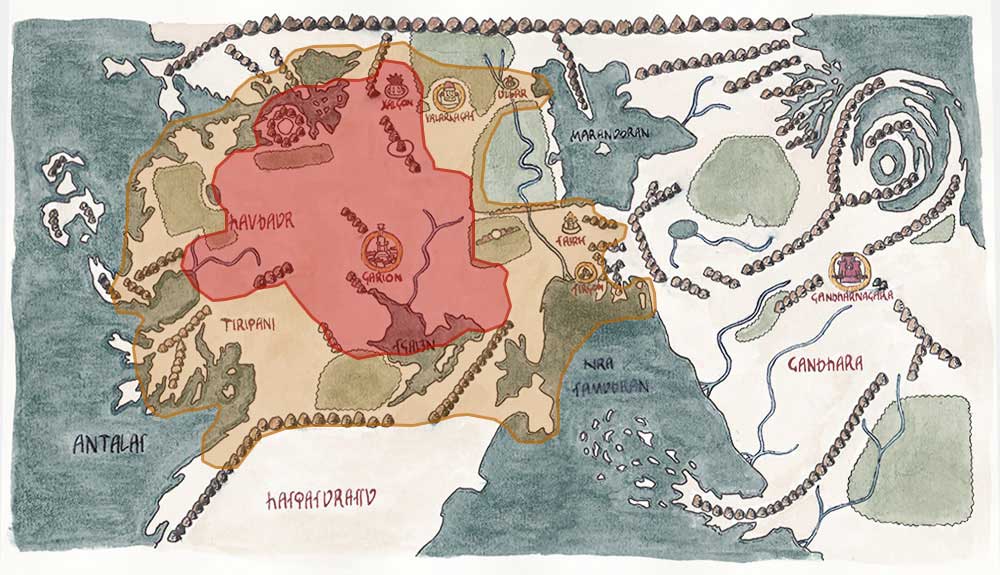

Vezanian is the old classical language in the Ancient West; it is the dialect of old manuscripts, enchantments, inscriptions, it can be seen in the fallen cities but also in classical literature. As the name itself suggests, it is the tongue of the Ancient Vezan, and till this day, many nations of the Vezanian race speak languages related to it. While Vezanian itself in its classical form is already a dead language, its newer versions are spoken in countries across the western continent – from the Free Land to Havdaur, from the Saiphates to Xalgon. Most of the time, a form of Vezanian script is used in writing (see picture on the right). The best known and most commonly used living form of Vezanian is Xalgonian and Garionian.

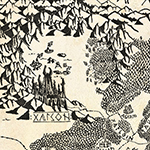

Xalgonian

Even the sworn enemies of the Dark City of Xalgon must admit the language of its inhabitants carries peculiar aesthetics and a bittersweet tone that as if contrasted with the reputation of its users. It is said Xalgonian is descended from the tongue of Ancient Vezan, an ancient realm at the northwest of Grand commonly presented by the Siranian historians as a babel of rumbustious destruction entirely fallen to darkness and demonic force. Who knows what the true story is.

Ancient Vezanian is descended from a yet older forefather: the tongue of the Zilaths, or the Rulers, themselves; a language with the power to command and whose words become reality. It is no coincidence that in contemporary Xalgonian, “word” and “thing” are still expressed by the same word: thabar.

In The Saga of Lundir, for instance, we encounter two names in Xalgonian: Me’awar, Lundir’s Xalgonian name, and Me’atham, the name the Zilaths themselves gave to Lundir’s brother, Valhun. Their meaning is easily decipherable; even the author of the saga is aware of the fact and mentions their translation in passing: me– is a prefix corresponding with our preposition “from, (out) of”; awar means “ash” and atham “dirt”. Therefore, the names mean (made) “of ash” and “of dirt”. Any expert on the Xalgonian culture will know these names are by no means accidental but, in fact, privileged – according to the Zilath teachings, it was precisely from the mixture of ashes and dirt the first man was created at the beginning of time. Zilabaoth then poured the blood of greedinessdesire and hunger into this ash-dirt blend; he breathed desire and thirst into it and infused it with a mind full of godly fear, thus giving rise to life. People were made to be Zilabaoth’s worshippers and were purposely created as sinful imperfect beings to highlight the greatness of their creator. This is what the ancient Xalgonian traditions tell us.

Garionian

(the text was taken from the Great Map of Grand)

While the development of Xalgonian has been influenced mostly by the tongues of the demon lords and the Dark Elves, Garionian is a far more everyday and open version of Vezanian. Garionian, named by the largest city in Grand, the ancient and splendid Garion, is a hearty and in many ways easy language with a great part of the vocabulary as well as some of its grammatical features borrowed from the language of the Dorns. Especially in its vocabulary, the language is very fond of loans. Owing to the vast commercial and political influence of Garion, the language plays the role of the lingua franca in Western Grand.

As mentioned before, the Garionian grammar is relatively simple, most of its vocabulary fairly international. Without going into too much detail, we can offer the reader a few illustrations from the language’s morphology, and a handful of words.

Garionian has four grammatical genders corresponding to the natural elements. Here, we label the genders by the corresponding Latin terms to draw an analogy with the terms masculine, feminine and neuter; however, our Latin terminology is merely a translation of the Vezanian terms:

- igninum denotes everything fiery, hot, burning, hurtful, intense; i.a. individuals of the masculine gender

- aquinum denotes everything related to water, everything with muffling or dampening qualities, everything healing and soft; i.a. individuals of the feminine gender

- aerinum denotes everything airy, ghost-like, intangible; i.a. ideas, abstractions, and concepts

- terrinum denotes everything solid, hard, static; i.a. inanimate objects, products, tools

The formation of these four genders seems to be a special innovation, probably under the influence of the Dornish languages; the original Vezanian only distinguishes between a “human gender” and “object gender” where objects are everything non-human, i.e., also trees and animals. This strongly dualistic approach is in stark contrast with the situation in Garionian where the nature is literary fragmentized, though not entirely systematically, into four different genders – animals and trees, evoking predominantly “soft” or “fine” impressions, are aquina; the beasts of prey are mostly ignina; weather-related phenomena are mostly aerina but if they are intense, for instance, a tornado or a blizzard, they may fall into the ignina category. Most of the fruit trees are aquina but once cut down, they become terrinum.

| singular | feature | translation | plural | feature | translation | |

| ign. | ‘ehś | -ś | fire | ‘ehim | -im | fires |

| aq. | mymah | -ah | water | mymoth | -oth | waters |

| aer. | ru’aq | wind | ru’aqyz | -yz | winds | |

| ter. | ‘athamu | -u | lump | ‘athamakh | -akh | lumps |

Apart from the singular and plural, the nouns have no further inflection. Syntactical relations we express with preposition and the word order are expressed with special prefixes:

| function | form | example | translation | funcion | form | example | translation |

| ablativ, “from/out of” | me- | medaru | made of rock | “like”, similitiv | qi- | qidaru | like a rock, rock-like |

| direct object | ‘a- | ‘adaru | (to see) a rock | posesiv, genitiv | tso- | tsodaru | of a rock, rock’s, rocky |

| indirect object | l-/le- | ledaru | to a rock | “in”, lokativ | f-/fe- | fedaru | in the rock |

| comitative, conjunction “and” | u-/w- | udaru | and rock | “for, because of”, causative | ‘er- | ‘erdaru | because of/for the sake of rock |

| “with”, instrumental | zy- | zydaru | with the rock | vokativ | jo- | jodaru! | rock! |

In Garionian there are two types of a definite article used according to the measure of respect the user wants to convey:

- In official documents, statements, and respectful communication between strangers, one uses the determiner ha– (where “a” becomes identical with the following vowel) – for instance, hadaru “the rock (respectfully)”, hy’ylonah, “the tree (respectfully)”.

- On the other hand, the common tongue or general language favours the use of the determiner –al suffixed to the word (where “a” is dropped if the word ends in a vowel); for instance, darul , “the rock”, ‘ylonahal, “the tree”.

Verbs in Garionian partly behave as nouns; the grammatical number and gender are distinguished according to the same categories. However, verb gender differs from that of the nouns: igninum corresponds to the active voice (“I teach someone”), terrinum to the passive voice (“I’m taught), aquinum to the middle voice (“I’m learning ”), while aerinum is used for intransitive actions (“it’s raining”, “it’s dawning”, “I’m singing”). However, when the action becomes transitive (“it’s raining cats and dogs”, “I’m singing odes), igninum is used instead.

Minislovníček

rock – daru

river – nissarah

tree – ‘ylonah

fire – ‘ehś

water – mymah

sea – jomah

day – ‘ahaś

night – lilah

truth – ‘ymt

lie – širuq

sun – ‘ośaś

moon – khozah

son – julś

daughter – julah

father – bore’ś

mother – bore’ah

man – ‘izelś

woman – ‘izelah

one – ‘ath

two – beth

three – de’eth

dog – qalfeś/qalfeh

bird – tsefir

fish – nunah

snake – nehhešah

eye – ‘ogir

hand – jagorś

sword – kharabś

chariot – rokabu

door – dylethu

house – bejuru

big – gofok

small – zilmi

good – tsaw

bad – ro’ekh

give – nadath

to go – qalah

to be – ‘ahaj

to have – waman

to say – qa’al

to see – zahar

to know – jawad

to want – hakhaš